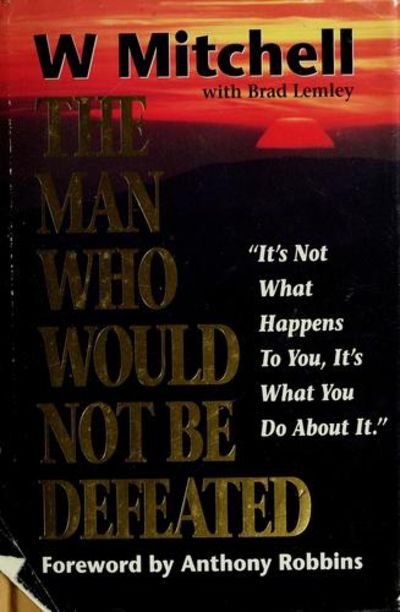

It's Not What Happens to You, It's What You Do About It Summary

5 Key Takeaways

Responsibility Over Blame Life’s circumstances are not always in our control, but our responses are. Looking for someone to blame is disempowering; taking ownership of how we respond is the first step toward healing and growth.

Perspective Shapes Reality There are no absolute links between external circumstances and happiness or misery. It’s the meaning we give to experiences—not the events themselves—that shape our lives.

Control is a Core Human Need Even in the face of extreme injury or adversity, regaining a sense of control—however small—can dramatically influence emotional and physical recovery.

Support Systems Matter Personal resilience is strengthened by relationships. Deep, maintained connections with others are essential in navigating difficult times.

The Power of Risk and Action Taking action, even imperfectly, builds momentum and opens opportunities. Fear of failure or perfectionism often limits growth more than actual obstacles.

Favourite Quote

“It’s not what happens to you; it’s what you do about it.”

Highlights

Page #13:

I have recognized the power that we have to change virtually anything and everything in our lives.

It’s not the conditions or the “externals” of your life that will determine your destiny.

What matters is the decisions you make about how your life is going to be—the decisions that will write the story of your destiny.Page #15: “Nothing, absolutely nothing, is absolute.”

Page #15: “Change what happens in your head, and the universe changes.”

Page #16:

“If he can be successful, I can.”

Nonetheless, whatever you want, you can achieve it, just as I have.

In fact, one of the secrets I reveal is that being pushy and generally obnoxious at the right times has been fundamental to my success.Page #3:

In 1971, if you were burned over seventy-five percent of your body, you were definitely dead. I was burned over sixty-five percent of my body, which put my chances around fifty-fifty.

Page #7:

There, I was in hot water almost immediately. For one, I had been smoking since I was twelve, and at Perkiomen, they were less than thrilled with that habit. Again, academically, I was a disaster. I spent most of that year receiving lectures from the headmaster and was eventually expelled.

Page #9:

And that December, I got married. My bride was Carol Kaleiwahea, who, at twenty-eight, was seven years older than me, and whom I had pursued with great vigor.

After we had been married about six months, I decided we needed to get divorced.Page #12:

I was always swimming in girlfriends, thanks to the cheap, shameless ploys for female attention that never failed.

Page #13: “Many of us fruitlessly aspire to be a”

Page #14:

cool, flawless, constantly happy, totally in-control person, but that is an idiotic aspiration that creates a lot of misery.

Real people get sad, angry, feel grief, and say things they regret.

If you cannot accept your negative aspects—if you dwell on them, wallowing in regret—you are actually reinforcing them, and you might never succeed in getting past them.

Second, there is no absolute relationship between any two variables. In other words, being rich, famous, and surrounded by friends does not automatically equal happiness; being poor, unknown, and alone does not automatically equal misery.Page #15: “The point is to take charge of your situation.”

Page #15: “Third, you are responsible for your life.”

Page #15:

There is never any point in looking for the bad guy, the rotten “other” upon whom you can heap blame for your wretched situation.

No matter how guiltless you may seem to be, no matter how carefully you document the unjust abuses heaped upon you, you are the only one who can turn your life around.

So you’ll do better if you adopt the belief, or at least explore the possibility, that at some level, you brought it on yourself.

Seeking the villain who ruined you is a pointless pursuit; it robs you of the energy you could be using to improve your life.

But the kernel of truth was here: you can only heal your experience.

If you wish to extricate yourself from the experience and get on with your life, you must use your energy in a productive way, and you can only do this if you take responsibility.

Hunting down folks to blame is not productive. Taking whatever lessons this experience taught you and moving on from there is productive. It is the only course that makes sense.Page #17:

I have heard that visitors, including tough guys with whom I had worked on the cable cars, would faint upon

Page #18:

Hearing the warm voices of friends through the midst of semiconsciousness was probably the main thing that kept me going at that stage.

Page #19:

This, in fact, is what makes the pain of being burned so extreme: you will die from fluid loss or infection if you are left alone, so you are never left alone. Something terribly painful is being done to you virtually every hour of the day, day after day.

Page #21:

Nurses who accept burn cases are a special breed, because it is so extraordinarily painful to care for the patient, and the patients often die. Even among these exceptional people, June and Nualan were among the best. During the four months that they took care of me, Nualan took six days off, and June took three days.

Page #22:

The normal, expected, even encouraged reaction would be to moan, wail, cry, curse God, sink into a funk, maybe even commit suicide.

But like the bumper sticker says, “Why be normal?” I thought of the support of my family and friends. I thought of my Marine Corps training. I thought about Morehouse and how there is no absolute relationship between any two variables. Once, I had fingers. Now, I didn’t. Whatever meaning this change had would be the meaning I gave it. I could see it as a catastrophe or as a challenge. I chose the latter.Page #23:

She did not know, but I knew, even then: the secret to survival was consciously not realizing how terrible it was. More than two decades later, I am proud to say that I still refuse to “know” how terrible it was. In other words, to adopt the social definition of what being so horribly burned “should” mean.

If you have a difficult situation in your life, I suggest you refuse to realize how terrible it is, too. How about realizing what can be salvaged? How about realizing what you have learned? How about realizing that the worst is behind you?

After a month of weakness and passivity, I decided to take control of my situation. I cannot overemphasize how important it is to do this. Numerous studies have shown that people will forego food, sleep, sex, and almost any other hunger you can imagine before they will give up control. Control and well-being are so intimately related.Page #24:

Again, he briskly told me he knew what was best and that I would not miss them at all.

The loss of control and the loss of two people who had become so important to me could have been fatal. I am a survivor, but at that moment, I did not need another test.Page #25:

I laughed. It hurt like hell, but I laughed. For the first time in two months, I found some humor in my life. At that moment, I began to gain some perspective. It may be that, at that moment, the seeds were planted of the message that I share with so many people around the world today: it’s not what happens to you; it’s what you do about it.

Page #26:

“Woooo,” I said softly. “That’s an interesting-looking guy.” Naturally, I was shocked.

But, somehow, I wasn’t horrified by it. I had my bedrock of information—that I would decide what to do about this, not society—and that held me together. Under it all, I had the strong sense that I would get through this.Page #27:

But without those doctors, nurses, relatives, and friends giving me their skill and their love, I am sure that even the most elegant, self-contained philosophical system could not have saved me. In particular, I was aided all along by Rita’s mother.

So, to the ideas I’ve already mentioned about coping and growing through adversity, let me add a crucial factor: support. We all need people who care. Almost anything can be borne if one feels surrounded by a network of friends and family, whereas a minor setback can derail a person who is trying to muscle through life alone.

And friendships don’t just happen; they must be actively started and actively maintained, or they wither. It took my utter helplessness to let me see this clearly, but we all have areas in which we are helpless. Whatever you are going through, do what you can on your own, but don’t be afraid to reach out for help. Putting both inner and outer resources together is an unbeatable combination.Page #31:

This was going to be my fate for the rest of my life. I had gotten somewhat used to it.

Now it was the world that was changing. For example, on the night of the accident, when my leather jacket was cut off my body, a book spilled out.

It was a book I had planned to give to a new lady I had met, and the odds had been high that we were going to spend the night together.Page #32:

By the time the awful sensitivity of the fresh burns passed, our sex life eventually returned to normal, but it was difficult. I felt completely impotent in general around women. At worst, I felt repulsive; at best, emasculated. But, because of Rita, that fear slowly passed.

Page #34:

When I said nothing, he got more abusive as he realized I was not going to fight back.

At that moment, we have more options than we can imagine; one good thing that comes from handicaps is that it opens one’s eyes to the reality of that.Page #35:

(I might add that it’s not pure coincidence that the man was poor and Hispanic. I have found since that it is Blacks, Hispanics, and the down-and-out who generally make eye contact with me on the street; perhaps out of some intuitive sense of sharing a position on the fringes of society. In the worst ghetto in America, I am not only without fear, but I feel welcomed.)

But I had an overwhelming desire to show them a vital truth: that someone who looks monstrous on the outside can be good, warm, funny, and caring on the inside—someone you might like as much as your best friend.Page #36:

I wanted to tell them something that a wonderful speaker and good friend shared with me much later—that the wrapping might have been damaged, but the gift inside was still in good shape.

I think at that moment I subconsciously resolved to share that message with people for the rest of my life.Page #37:

Almost immediately, I started ground school, aiming to fly again. I couldn’t feed myself, but I refused to focus on just surviving. I planned to thrive, and for me, that meant flying.

Page #38:

Again, the only solution is simply to take charge.

Page #42:

This highlights the strangeness of our legal system, which rewards helplessness and penalizes success. I had no problem with suing.

Page #43: “He got $450,000, thanks to Pat Coyle, from the company.”

Page #44:

He was convinced he had all the answers, and his therapy-group participants knew nothing.

These people were clearly addicted to the idea that they were sick.

You can spend your whole life focusing on the worst aspects of your life if you choose to. Do you want to spend all your time focusing on how bad your relationship, job, or appearance is, or do you want to focus on how good it can become?

The idea of self-help groups should be just that—to help people understand that the decision is up to them.

But wallowing in angst is not my thing, and that’s what these sessions were all about.Page #45:

I call that my tipping point moment. I realized that there was nothing I could not do.

I had conquered my last limitation. I still could not do buttons—I suppose I could not be one hundred percent independent—but psychologically, I was one hundred percent. I had finished the cycle of being burned.Page #46:

I believe in the healing power of love, but beyond that, I don’t know.

Page #47:

Crested Butte, Colorado, is an old coal-mining town nestled at an altitude of 8,885 feet in a sparsely populated valley. It’s twenty-five miles as the Cessna flies from Aspen, but 217 miles by paved roads, which illustrates its remoteness.

Page #49:

I bought a house, one of the nicest in town that had been built in 1886.

I bought a few house lots which promptly tripled in value, built a huge log building with apartments in it, and generally became a successful entrepreneur.Page #50:

I did it all on gut feeling, and it was the smartest move, financially, I’ve ever made.

As the energy crisis continued to intensify, the company could barely keep up with demand. It became the second-largest private employer in the state of Vermont, with dealerships in all fifty states (yes, even Hawaii). My life was far better than it had been before I was burned. Suddenly, I was a millionaire.

The lesson? How many things do we say no to because they are not guaranteed? How many of us are not willing to risk our time, energy, or money for success?Page #50: “The idea”

Page #51:

The idea of being a risk-taker applies to more than just financial wealth. It applies to emotional wealth as well. Many people ask for sure things and wind up with no things.

Almost everyone who has become a great success in our society has been willing to take risks, and when they failed, were willing to try again, and again, and again.Page #53:

“Adversity reveals genius.” —Horace

Page #57:

But now I had little time to mope. My support system was far bigger than it had been when I was burned. Literally hundreds of folks from Crested Butte made the five-hour drive to see me. They came just to tell me they cared and to encourage me.

Page #57: “I came to see, more than”

Page #58:

ever before, how friendships are investments that offer protection in a crisis that no insurance policy can give.

But maybe I had known what I was talking about. Being burned to a crisp had not ruined my life. In many ways, it had made me grow, change, and improve in ways which I could not have dreamed.

If there was no absolute relationship between being burned and being miserable, then it followed that there was no absolute link between being paralyzed and being doubly miserable. This experience would be what I made of it; not what others thought I should make of it.

I decided to take charge again. Taking charge had literally saved my life after I was burned.

There are no absolutes in the world. If you build a barricade of absolutes, even likely pieces of happiness can be walled out. Much more so, the unlikely pieces.Page #59: “This is denial and does no one any good.”

Page #59:

Lying in bed wishing for recovery simply atrophies muscles, angers therapists, and boosts already astronomical hospital bills.

Third, I would take the best counsel I could get, but I would make the decisions. By now, I was a firm believer in control and its role in a healthy life. No one would do anything to me unless they had explained the need for it and I had agreed.Page #61:

“Destiny is not a matter of chance; it is a matter of choice.” —William Jennings Bryan

It is not a thing to be waited for; it is a thing to be achieved.Page #63:

I chose to get on with my life.

Page #66:

It’s advice that applies to everyone. For all of the things we cannot do because we’re not gorgeous, rich, or adored, there are infinitely more things waiting for us to do, most of which we’ve never even considered—far more than you could do in a thousand lifetimes.

If, in one lifetime, you did five hundred of them, you’d be an Edison or an Einstein.

So often, we do nothing because we feel that we cannot do enough. That’s the greatest fallacy in life, because the big things are, in fact, usually a series of little things.Page #69:

So, I was back. While parts of life were good, there were multiple frustrations.

The old freedom I’d had to ski when I felt like it, carry in wood, shovel the walk, and be completely independent was no longer available.

But my friends were still there, and they helped to reduce the frustration.

I bought myself a motorhome and had another friend, Gordon Roberts, outfit it for me. After he learned that I had broken my back, he left school in San Francisco and hitchhiked to Denver to be with me in the hospital simply because he was a friend and wanted to help.Page #69: “I”

Page #70:

Within six months of returning, I flew again with a friend, just to see if I was afraid. I wasn’t. It wasn’t the airplane that had bitten me, after all, but my poor judgment.

Page #70: “I had learned a basic truth: nothing is absolutely safe.”

Page #71:

Live your life, take all necessary precautions, but follow your heart.

Sally Jesse Raphael, on her television program, once asked me if I ever wished I had exercised a little more caution in my life. I told her, “In my office, I’ve got a poster on my wall that lists the BE-Attitudes. There are things such as Be Loving, Be Warm—but nowhere does it say, ‘Be Careful.’

I’m not a reckless person. I believe in the value of life. But you can’t spend your life in a cave, keeping safe from risk.

The greatest risk, in my opinion, is taking no risk at all.”Page #73:

For the next three months, I devoted every ounce of energy to running for the job. I studied the sewer system, the garbage system—did we need our first traffic light?

Page #76:

And we fought on legal fronts. We dug up an obscure, one-hundred-year-old state law that gave cities the right to control their watersheds. We set up the Crested Butte Municipal Watershed and began writing restrictive regulations, even inventing a permitting process, because the mine would be smack in the middle of that watershed. If there is one thing that the powers-that-be respect in the West, even above mining, it is water. The town was behind me, too; I won reelection in 1980, capturing ninety percent of the vote.

Page #77: “By the time they quit, we had barely started.”

Page #78:

The planet, I remain convinced, has too few defenders, and I often wonder why that is. Is it because no one taught us to care? Is it because saving it, even a piece of it, seems so hopeless against all the forces arrayed against it—against all of the incantations and incarnations of that hideous philosophy, “bigger is better?”

Someday, I hope we find out. The planet can no longer afford to have its most potent and influential information technologies controlled by forces that put the bottom line above all other values.

The real issue in the AMAX fight was, as Congresswoman Pat Schroeder of Colorado is fond of saying, “You’ve got to stand for something, or you are going to fall for everything.”Page #83:

I am, by nature, a sensual person—a toucher, a holder, a cuddler. While paralysis cancels physical sensation below the waist, the real sex organ—the brain—is above it.

Page #87:

I decided to do it because of a basic rule I used to govern my life: the only way you can really fail in life is never to try.

Page #90:

But I tell people today that I didn’t lose that race in 1984. I tell them that, yes, my opponent got a few more votes than I did, and that hurt, but the wonderful lesson I learned is that the only losers are the ones who don’t get in the race.

I love to quote Theodore Roosevelt, who said that the only real losers in life are those people who end their lives “having tasted neither victory nor defeat.”Page #94:

The whole idea behind this is that if you can walk on fire, you prove to yourself that you can do damn near anything, that any limitations in your life are probably self-imposed.

I had already figured that, but in my own way, so who needed this?

I firmly believe that most barriers are self-imposed. We first get them from society—you can’t do that, that’s immoral, that’s crazy, no one in our family does that, and so on—but we forget that we have the power to accept or reject these barriers.

We treat them as if they are immovable, immutable, when, in fact, they may be silly, cause unnecessary misery, or just be plain nonexistent.Page #97:

He still wasn’t impressed. He wasn’t satisfied because I wasn’t doing it in the only way that he had learned it should be done.

I was not playing by the established rules. I was not solving the problem the way everyone else had solved it.Page #100:

But I wasn’t stuck long. I had two things going for me: One, I had committed myself to becoming a public speaker. Commitment is the first move of anything we wish to accomplish. A friend, guide, and hero don’t have to

Page #101:

The second was that, coupled with my commitment, I understood how important it was to act—to do something even if I was not sure it was the right thing.

Watt Anderson, the editor of Parade Magazine and a good friend of mine, has written a book called The Greatest Mistake of All, in which he says the greatest risk is to take action. Looking back on my life, I saw that this had been the key to my success.Page #102:

Another way of looking at it is described by Ken Blanchard, of One-Minute Manager fame. He talks about people who go through life as if they are playing a tennis game by watching only the scoreboard and never the court.

He often asks the question: “When you take your last breath, are you going to be sorry you haven’t made more money?”Page #103:

Today, Annie and I are good friends and are groping for a new way to relate to each other after our divorce.

Page #143:

Join a group that’s already doing something. Don’t just join—participate. Think about what you care about—such as the environment or people who haven’t had the opportunities you’ve had—there is a lot to do.